Studying in a foreign country is a unique academic challenge, especially when navigating it as a family. I vividly remember our time in Vietnam with kids; while the children were settled into a local international school in Hoi An for their primary education, we were busy managing our own professional work as a digital nomads. Having those dedicated hours while the kids were in class was our “engine room”—it was the only way we could stay productive enough to enjoy the “slow life” of Vietnam once the school day ended.

Unlike traditional campus settings, international study introduces variables that directly affect concentration, memory, and time management. Success is about how experiential exposure can be structured to support academic achievement.

- Cognitive Load and Environmental Adaptation

- Structured Time Allocation and Academic Prioritization

- Active Learning in a Cross-Cultural Context

- Environmental Context and Memory Encoding

- Energy Regulation and Academic Performance

- Decision-Making and Opportunity Selection

- Social Support and Academic Accountability

- Reflective Integration of Experience and Theory

- Planning for High-Intensity Academic Periods

- Conclusion

Cognitive Load and Environmental Adaptation

Relocating to a new country increases cognitive load. Students must navigate unfamiliar systems, interpret new social norms, and often communicate in a second language. According to cognitive load theory, working memory has limited capacity. When excessive mental resources are allocated to adaptation, fewer remain available for academic processing.

To mitigate this effect, students should establish stable routines early in the semester. Just as we found stability by aligning our work and study sprints with the children’s school schedule in Hoi An, creating fixed “deep work” blocks reduces decision fatigue. Fixed study hours, consistent study locations, and structured weekly planning reduce decision fatigue. When basic daily actions become automatic, cognitive resources can be redirected toward complex academic tasks such as analysis, synthesis, and problem solving.

Routine does not limit exploration. Rather, it creates a cognitive foundation that supports it.

Structured Time Allocation and Academic Prioritization

Effective academic performance abroad depends on intentional time allocation. Success requires consistent planning and monitoring. Students should start by mapping all major deadlines to identify low-intensity periods suitable for travel or cultural engagement.

During high-pressure weeks, maintaining this balance often requires strategic delegation. Many choose to hire an expert on the page https://papersowl.com/write-my-philosophy-paper to handle specific research demands and keep their schedule on track.

At the micro level, weekly study blocks should be defined by objectives rather than duration. Completing a literature review or solving quantitative problems is more effective than undefined study time. Task-specific goals increase productivity and reduce procrastination.

Active Learning in a Cross-Cultural Context

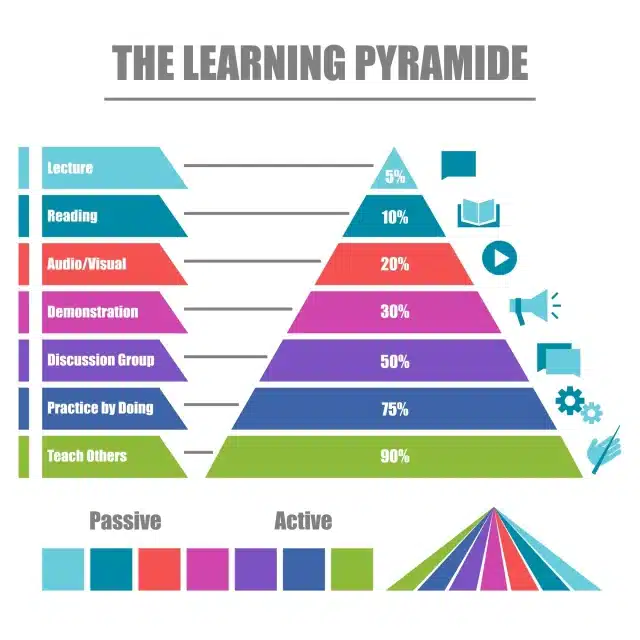

Passive review techniques, such as rereading notes, are insufficient in high-stimulation environments. Students studying abroad face increased distractions and therefore benefit from active learning strategies that enhance retention efficiency.

Evidence-based techniques include:

- Retrieval practice through self-testing

- Spaced repetition across multiple sessions

- Elaborative interrogation by explaining concepts in one’s own words

- Application-based practice such as case analysis or problem-solving exercises

A foreign environment can strengthen these methods. For instance, language students can practice retrieval through real-world conversations. Political science students can compare classroom theory with local policy debates. Business students can analyze local market structures and consumer behavior.

Experiential exposure, when consciously linked to coursework, transforms exploration into applied learning.

Environmental Context and Memory Encoding

Research in contextual learning suggests that varied study environments can enhance encoding by creating multiple associative cues. Studying in different libraries, parks, or cafés may strengthen memory retrieval by linking material to diverse contexts.

However, environmental variation must not compromise focus. Students should evaluate whether a location supports deep work. If social interaction interferes with concentration, quieter alternatives are preferable.

The key principle is intentionality. Environment should be selected based on academic function, not novelty alone.

Energy Regulation and Academic Performance

Physiological regulation directly influences cognitive outcomes. Sleep deprivation impairs working memory, attention, and executive function. In an international setting, irregular schedules due to travel or social events can significantly disrupt academic efficiency.

Maintaining consistent sleep patterns, balanced nutrition, and moderate physical activity supports neurocognitive performance. Exploration often involves increased walking and exposure to natural environments, both of which are associated with improved mood and attentional restoration. When managed responsibly, travel-related activity may enhance rather than diminish academic capacity.

Energy management, therefore, should be viewed as an academic strategy rather than a lifestyle preference.

Decision-Making and Opportunity Selection

A common psychological phenomenon among international students is the perception of scarcity, often described as “fear of missing out.” The belief that every opportunity is unique may lead to overcommitment and academic neglect.

From a self-regulation perspective, effective students apply selective engagement. Opportunities are evaluated based on timing, workload, and alignment with personal or academic goals. Strategic refusal of certain activities preserves cognitive and temporal resources for high-value experiences.

Selective participation does not reduce cultural immersion. Instead, it increases its depth and sustainability.

Social Support and Academic Accountability

Peer networks significantly influence academic outcomes. Forming study groups with academically motivated classmates provides accountability and collaborative reinforcement of material. Group preparation before planned travel can ensure workload completion without sacrificing social cohesion.

Faculty interaction is equally important. Consulting instructors regarding expectations, assessment criteria, and feedback mechanisms reduces ambiguity and improves performance. International students may hesitate to initiate such communication due to cultural differences, yet proactive engagement correlates strongly with academic success.

Structured social support systems stabilize academic progress amid environmental change.

Reflective Integration of Experience and Theory

One of the most academically valuable aspects of studying abroad is the opportunity for reflective integration. Reflection transforms experience into structured knowledge.

Maintaining a reflective journal can support this process. Students might document observations related to course themes, compare theoretical frameworks with lived realities, or analyze cultural phenomena using academic terminology.

For example, sociology students may observe patterns of social stratification. Economics students may examine price variation and consumer behavior. Literature students may analyze local narratives and linguistic expression.

Reflection consolidates experiential learning into academically relevant insight.

Planning for High-Intensity Academic Periods

Examination weeks and major submission deadlines require reduced extracurricular engagement. Anticipatory planning is essential. Travel and large-scale exploration should be scheduled during institutional breaks or low-demand intervals.

When travel near deadlines is unavoidable, preparatory work must be completed in advance. Drafting outlines, organizing research materials, and reviewing core concepts prior to departure minimizes cognitive overload upon return.

Strategic foresight distinguishes sustainable balance from reactive crisis management.

Conclusion

Studying effectively while exploring a new country requires deliberate integration of structure and flexibility. Academic performance is not inherently threatened by cultural immersion. Rather, it depends on how students regulate cognitive load, manage time, apply active learning techniques, and maintain physiological stability.

When exploration is aligned with academic objectives, it enhances analytical depth, intercultural competence, and applied understanding. The goal is not to compartmentalize study and travel as competing domains, but to conceptualize them as complementary dimensions of higher education.

International study, when approached strategically, develops both intellectual mastery and global awareness. The result is not merely successful academic performance, but comprehensive scholarly growth grounded in lived experience.

Lived in England since 1998 and travelled the world since 2005, visiting over 100 countries on 5 continents. Writer, blogger, photographer with a passion for adventure and travel, discovering those off beat places not yet on the tourist trail. Marco contributes the very best in independent travel tips and lifestyle articles.